A short history of Vendor Finance in Australia

Vendor Finance has been used for selling real estate in Australia for a very long time. In fact, for long periods of time banks were reluctant to lend for residential purchases, preferring instead to finance business and investments because they offered better profits.

1870s – 1920s

In the land boom years of the 1870s and 1880s which were fuelled by the gold rushes and boom time exports of wool and wheat, property developers subdivided land for sale to meet demand. Some blocks of land were sold to buyers who build homes upon the land; other blocks of land were sold to property speculators who purchased the land for re-sale at a profit.

Then as now, bank finance was not freely available to buyers on vacant blocks of land, because banks were not comfortable with recovering their money if they lent on vacant house blocks of land.

Therefore, in the 1870s and 1880s, to sell their land property developers offered vendor finance terms which were typically ¼ of the price as a deposit, ¼ of the price after six months, ¼ of the price after 12 months and the final ¼ of the price after 18 months. Interest was payable at 6% p.a. on the outstanding amounts.

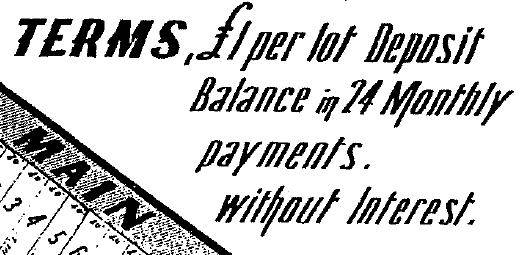

In the early 1890s, many banks collapsed as the weight of property speculation and the great drought took their toll. Variations appeared to the vendor finance model. For example, here is a plan of subdivision at Blacktown, near the railway station, dated 1895.

You will notice that the land is for sale, not at a price, but on vendor finance terms being a £1 deposit, followed by 24 monthly instalments of £1 each. The total terms price was £25 for the land, and it is safe to say that the cash price would have been less! But more importantly, the property developer was able to sell the land because they offered terms to suit the buyer’s pocket, in a climate where no bank loans were available.

1901

In Phillip Street Sydney, James Edward Hogg authored a book of Conveyancing Precedents and forms for use in New South Wales and other States and Colonies in Australia. Included was a precedent instalment payment clause, for vendor finance of real estate, which I reproduce –

Instalments. The purchase money, with interest thereon, or on the unpaid part thereof, at £-- p.c. p.a. from the – day of ---, shall be paid by – equal half-yearly instalments of principal amounting to £-- each, payable on the – day of -- & the – day of – in each year, the first to be paid on the said – day of --, with the addition to each instalment of the interest on the portion of the purchase money remaining unpaid, ….

Another vendor finance precedent in the book is for the conveyance of property following upon the exercise of an option to purchase contained in a lease – the title of the precedent is –

CONVEYANCE of a REVERSION EXPECTANT on a LEASE to the LESSEE, who purchases under an OPTION OF PURCHASE given him by the lease

1900 -1927

Between 1900 and 1927, the practice of selling land on vendor finance terms was widely used and accepted, with land in Sydney suburban locations such as North Sydney, Chatswood, Hornsby, Centennial Park, Randwick, Potts Point and Heathcote advertised for sale on terms.

The vendor finance terms were typically 1/5 th (i.e. 20%) of the price paid as a deposit, followed by 4 equal annual instalments of 1/5 th (i.e. 20%) each. Interest was payable at 5% pa on the outstanding amounts.

1927

With this high level of vendor finance activity, it is not surprising that the profits from vendor finance came to the attention of the Federal Commissioner of Taxation, and that a legal dispute arose.

In 1927, the High Court of Australia considered the tax consequences of two forms of Vendor Finance, in the legal case of:

The Federal Commissioner of Taxation -v- Thorogood

which is reported in: (1927) Volume 40 Commonwealth Law Reports at page 454.

The facts were:

James H Thorogood carried on the business of buying land, subdividing it into allotments and building houses on them, selling these as house and land packages.

Thorogood sold some house and land packages where he ‘funded’ the whole of the price with seller finance on terms consisting of - a deposit paid in cash which was paid to Thorogood, with the balance price payable by instalments over several years. These sales were documented by a Contract for Sale, which continued for several years, with Thorogood retaining the legal title to the property in his name until the Contract for Sale was completed by payment of the final instalment. Today these are known as Instalment Contracts.

Thorogood sold other house and land packages where he ‘funded’ a part of the price with seller finance on terms which consisted of - , the purchaser paying a deposit to Thorogood, an external financier funding a large part of the price secured by first mortgage, which was paid to Thorogood, with the balance of the price payable funded by Thorogood, who took as security a second mortgage over the property. These sales were also documented by a Contract for Sale which was completed in the normal time. Legal title to the property was transferred immediately to the buyer. The documentation for the seller finance took the form of a second mortgage in favour of Thorogood which was registered, ranking after a first mortgage from the external financier. Today these are known as Deposit Finance arrangements.

In both cases, interest was payable on the amount payable and owing to Thorogood.

The dispute:

The Federal Commissioner of Taxation assessed Thorogood to pay income tax on the whole price payable under the Contract for Sale in the year the Contract for Sale was entered into, even though in both cases, payment of part of the price was deferred until future years. Thorogood objected to the tax assessment and contended that he should only pay tax on the parts of the price for which payment was deferred until in future years in the future years in which payment was actually received.

The decision:

The High Court did not decide the dispute - it decided only that it was possible to take either view of the tax consequences of the transaction, depending upon the facts, and in particular, whether the taxpayer was in the business of providing vendor finance.

For our purposes, the important point is that the legality of both forms of vendor finance was accepted by the High Court of Australia.

1950s – early 1960s

- The use of vendor finance continued to fluctuate according to social and economic conditions and the availability of bank and non-bank finance.

- The supply of housing real estate became scare towards 1950, unable to meet the demands or veterans from World War II wanting to settle down an raise a family, as well as the large numbers of migrants coming to Australia wanting to do the same. This drove up the price of building materials and housing, which meant that saving the money to purchase real estate without borrowing was no longer feasible. But who was to provide the finance? Answer – the vendor!

- In the 1950’s and early 1960’s, land for housing was subdivided and sold on vendor finance terms of up to 5 years, with instalments paid monthly. The reason vendor finance was used was that the banking system did not usually provide loans for the purchase of blocks of land for housing.

- Therefore, in the 1950’s and early 1960’s, most young couples looking to build a home would purchase a block of land to build a home upon, from a property developer ‘off the plan’ in a land subdivision, using the terms finance form of vendor finance. Once the land was paid for, they would borrow the money to build their home from a bank.

- An example, here is a newspaper advertisement for the sale ‘off the plan’ of housing block land near Kiama south of Sydney, dated 1957, where terms were offered.

You will notice that terms are offered over 3 years.

- In 1961, there was a credit squeeze and many land subdividers went broke, leading to a tightening of the law applicable to vendor finance. Laws were passed in many of the States to restrict vendor finance.

- In the mid 1960s, the Commonwealth Government decided to make it easier for banks to lend for housing, and so bank finance became more readily available.

- These two events led to decline in the use of vendor finance.

1970s – 1980s

- In the late 1960’s, 1970’s & early 1980’s, home builders became major users of vendor finance to sell house and land packages to young couples.

- In those times, to obtain bank finance to purchase a home, a buyer would need to demonstrate a 12 months savings record and have a 25% deposit because the banks would only lend up to 75% of the value of the home.

- Home builders therefore sold house and land packages on an Instalment Contract, with payments mirroring a bank loan. This enabled to builder to obtain finance to build from their finance company. After twelve months, the builder would “cash out” the Instalment Contract, by transferring the Instalment Contract to their finance company.

- Generally after twelve months, the bank would be satisfied that the payments made by the buyer constituted a satisfactory payment/savings record, and so might then provide standard mortgage finance to the Purchaser to pay out the finance company.

- It is interesting to note that the NSW Department of Housing has had a policy to use the Instalment Contracts form of vendor finance to sell houses to its tenants since the early 1970’s, with 40 year terms on a 25% deposit being common. The same policy has applied in other States, such as South Australia.

Mid 1980s to date

- In the mid 1980’s the Commonwealth Government deregulated the banking system, which resulted in an influx of foreign banks offering housing finance.

- From the mid 1990s until the Global Financial Crisis (the GFC) in 2008, non-bank lenders, also known as securitised lenders, sourced loan money from the money markets especially in the USA and went from 0% of the home loan market to 20% of the home loan market.

- During this period of between mid 1980’s to the mid 2000s, increasing availability of home loan finance from the banks and the non-bank lenders made vendor finance shrink to a rump of what it was. By the mid 2000s, driven by competition, loan finance of up to 95% of valuation with minimal savings record was available to the employed and the self-employed.

- In the 2006 Australian Census, the Australian Government Statistician included

Question 56 -

Q Is this dwelling: Being purchased under a rent/buy scheme?

A 1.2% of Australians ticked “yes”.

The answer to this question underestimates the houses financed with vendor finance because it is restricted to rent to buy and instalment sales and because these last a short time – often 3 years, and are used as a stepping stone to bank finance.

The question was repeated in the 2011 Australian Census. - The GFC has seen the demise of the non-bank lenders and Basel II has put the shackles on bank lending, leaving the 18% of the home lending market that the non-bank lenders had serviced, without finance.

- Some of this 18% of the home lending market will not exist due to a decline in demand for housing, but as for the rest, represents an obvious market for vendor finance.

- In summary, there is an unsatisfied demand for vendor finance which has become apparent amongst buyers with low deposits, buyers who have their own business or trades and buyers whose credit rating is impaired, who do not qualify for loans from the banking system.

1 July 2010

- On 1 July 2010, the National Consumer Credit Protection Act came into force. This Act is a Commonwealth Act of parliament, and consolidates the laws governing consumer credit in Australia. From 1 July 2010, ASIC (the Australian Securities and Investments Commission) is the responsible governing body.

- This Act covers two forms of vendor finance, namely Instalment Sales and Deposit Finance. It does so by making them explicitly subject to the National Consumer Credit Code.

- The Act also provides that if a person is engaged in the business of providing these two forms of vendor finance, they must hold a National Credit Licence.