The Trivago website creates the impression that it quickly and easily identifies the cheapest available hotel room responding to a consumer’s search.

But is the impression a transparent comparison of rooms, or is it manipulated and false?

The Federal Court of Australia has found that Trivago misled the public by promoting hotels as having cheapest rooms when it was true only 33.2% of the time. The Court will impose pecuniary penalties on Trivago for contravening the Australian Consumer Law.

The decision is Australian Competition and Consumer Commission v Trivago N.V. [2020] FCA 16 (20 January 2020) (Moshinsky J).

In this article, we review the Court’s reasons as to how the Trivago website contravened the Australian Consumer Law.

The Trivago Business Model

Trivago N.V. is a foreign company, incorporated in the Netherlands. It carries on business in Australia by conducting an online search and price comparison platform for travel accommodation. Trivago has an Australian website.

Consumers use the website to quickly or easily identify the cheapest rates available for particular hotel rooms. They do not pay a fee to access the Trivago website.

The Trivago website acts as a metasearch site and not as a direct booking site. If a consumer clicks on an offer, they are taken to the booking site where they complete the booking.

Trivago interacts with the Online Booking Site’s databases and displays accommodation offers in response to consumers’ searches. There are currently 400 Online Booking Sites which use Trivago. They are either travel agencies such as Expedia, Wotif.com. Hotels.com and Amoma or accommodation providers such as hotels and serviced apartments.

The Sites pay Trivago a fee, referred to as a Cost Per Click (CPC), if a consumer clicks on their offer on the Trivago website. The CPC is not fixed. There is a minimum CPC determined by Trivago, but Online Booking Sites bid higher amounts to improve their exposure. The CPC is Trivago’s principal source of income.

The Trivago website

The Landing Page displays a selection of hotel rooms and the Trivago Logo. It had a slogan “Find your ideal hotel for the best price” which was later changed to “Find your ideal hotel and compare prices from many (different) websites”. These were the Lowest Rate Statements which the Court found to be misleading. These statements were repeated in television advertisements.

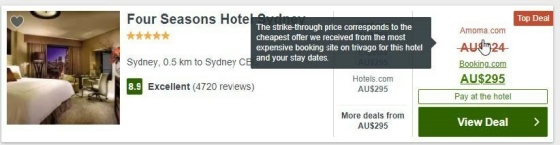

The Initial Search Results Page displays search results for the city or region, stay dates and room type the consumer has selected. For example:

In this listing, note the Strike-Through Price (the Red Price), and the Top Position Offer in green of $295 appear above the “View Deal” click-out button which takes the consumer to the Booking.com website. Note also the Hotels.com offer which appears to the left in grey and in a smaller font. Finally note the “hover-over” which explains the Strike-Through Price. The Court found this display to be misleading.

The Findings

The computer science experts agreed that:

- The Trivago Top Position algorithm calculates a “composite score” from these inputs: the offer price, the CPC, the priority modifier; the hotel position, average historical price, historical click-through rate; and the minimum price, maximum price, minimum priority CPC, maximum priority CPC, minimum gain and maximum gain. Non-price attributes are not used in the algorithm, such as free breakfast, refundable tariffs, bed size, free Wi-Fi and Pay at Check-in.

- Trivago did not disclose the ‘weights’ used for the inputs in the algorithm, and did not call any employees to explain how it worked. The Court found that the CPC was a very significant factor, and also that any offers which were lower than the minimum CPC were filtered out.

- Higher priced hotel offers were selected as the Top Position Offer over alternative lower priced offers in 66.8% of listings. The most common reason was a difference in CPC paid. Conversely, the Top Position Offer was the cheapest offer in only 33.2% of listings.

The consumer behaviour expert evidence was that:

- Trivago used the decoy (or attraction) effect by positioning the higher priced option in red next to the Top Position Offer – the strike-through reinforces the advantage.

- Consumers are used to believing that the comparison price will be for the same room.

- Many consumers are likely to interact only briefly with the website.

- The layout of prices, be it font sizes or colours, has a significant impact on user behaviour and, thus, on conversion.

For more detail on this evidence refer to the Marketing Commentary at the end of this article.

Contravention of the Australian Consumer Law

The relevant class of consumers was members of the public looking to book accommodation online. They are assumed to have some familiarity with using the internet and making bookings online, but have not used Trivago before.

In the period 1 December 2016 to 3 January 2018, there were 20,039,530 sessions on the Trivago website where the Top Position Offer for a hotel listing was clicked.

The ACCC alleged four breaches of the Australian Consumer Law. The Court found in favour of the ACCC on all four, as follows:

- Cheapest Price Representation was made when the words “best price” are used, which is synonymous with “cheapest price”. The whole point of the Trivago website was to help the consumer quickly and easily identify the cheapest price for the hotel.

The Court found that Trivago misled the public as to the nature, characteristics and suitability for purpose of the accommodation search service provided by the Trivago website by making the Cheapest Price Representation. The reasons included that the Top Position Offer was incomplete as the website did not display CPC bids less than the minimum threshold set by Trivago, and in only 33.2% of cases was the “best price” the cheapest on offer.

- Strike-Through Representation was made when a price strike-through appeared. The implicit representation was that the Strike-Through Price and the Top Position Offer were, apart from price, ‘like for like’ in terms of the same room category. The hover-over did not dispel the impression because it did not state that the Strike-Through Price may relate to a different room category.

The Court found that Trivago had misled and deceived the public by the Strike-Trough Representation.

Later on, Trivago used a Red Price Representation instead of a Strike-Through Representation. This did not alter the Court’s finding.

- Top Price Representation was made when Trivago represented that the Top Position Offers were either the cheapest available offers or that they had some other characteristic which made them more attractive than any other offer for that room.

The Court found that the presentation of the Top Position Offer in the far right column in green, in a relatively large font, with white space around it and above a green “View Deal” button, created the overall impression to the consumer that this was the best offer for the hotel room, either in terms of price or some other characteristic.

The Top Position Offer determined by the algorithm is not the cheapest offer for reasons given above. Nor is it more attractive because the Top Position algorithm does not use non-price attributes of the offers to determine the composite score. The hover-over did not dispel the impression because it did not disclose the significance of the CPC in the selection of the Top Position Offer in the algorithm.

The Court found that Trivago had misled and deceived the public by its conduct and by its representations in that the Top Price Offer was not the cheapest offer for the room, nor did it have some other characteristic that made it more attractive than any other offer for the room and that the comparison was not like for like in terms of room type.

- Additional conduct allegations were made when representations were made that the Trivago website provided an impartial, objective and transparent price comparison to identify the cheapest available offer for a particular (or exact same) room at a particular hotel. This applied especially to the television advertisements.

The Court found that Trivago had misled and deceived the public by its conduct and representations because the search selection was heavily influenced by the CPC, that is, the amount the booking site or hotel paid Trivago if the consumer clicked on an offer.

Note: Not all of these findings applied for the whole period under examination, which was between 1 December 2016 until 13 September 2019, because Trivago made a number of adjustments to its website during that period.

What’s next?

The Court will set a hearing in relation to relief, including pecuniary penalties.

The ACCC made these comments in its media release after the decision Trivago misled consumers about its hotel room rates (21 January 2020)

“We brought this case because we consider that Trivago’s conduct was particularly egregious. Many consumers may have been tricked by these price displays into thinking they were getting great discounts. In fact, Trivago wasn’t comparing apples with apples when it came to room type for these room rate comparisons,” ACCC chair Mr Sims said.

“This decision sends a strong message to comparison websites and search engines that if ranking or ordering of results is based or influenced by advertising, they should be upfront and clear with consumers about this so that consumers are not misled,” Mr Sims said.

Marketing commentary by Michael Field from EvettField Partners.

Consumer trust in online information is at an all-time low, largely driven by concerns about data collection, privacy and use of data by search engines and social media platforms.

That being said, consumers still want to be able to, and should be able to trust the information they source online from purportedly reputable vendors, especially if they intend to rely on that information to make purchase decisions. As such, consumers will rely on the brand, reputation and marketing of online price comparison sites to assess the trustworthiness and reliability of the information provided.

Trivago have done themselves and the broader online price comparison website category a huge disservice by deliberately deploying manipulative marketing strategies to deceive consumers, misusing the trust consumers place in their brand in the process.

The judgement relied on expert evidence from Professor Slonim to examine the consumer marketing perspective. To summarise his evidence, Professor Slonim dispels the myth that consumers are ‘maximizers’ who gather all of the available information on all of the available options to come to a rational decision to ‘optimise’ their purchase decision.

As consumers are time poor, and flooded with choices, there is a trade-off that takes place in the mind of the consumer whereby they aim to minimise the amount of time spent searching and comparing, especially if the perceived benefit is not high enough to justify the investment. For example, it may not be worth spending an additional hour online searching and comparing prices if the additional saving is likely to be worth less than the time spent searching.

Trivago would have, or should have known that their actions would be likely to deceive consumers. There was a clear commercial benefit for Trivago to maintain the deception as they continue to earn CPC revenue from advertisers willing to pay a premium for position.

The casualty in this judgement is consumer trust. Marketers would be well advised to heed the lesson, review their marketing strategies and ensure they are compliant with the relevant Australian consumer laws. This is especially true for international brands wishing to enter the Australian market.