Just how hard it is to extinguish a right of way for non-use was recently demonstrated in the decision of Sheppard v Smith [2021] NSWSC 1207 (23 September 2021), a decision of the Supreme Court of New South Wales (Parker J).

Background

The story began in January 1883, when Miss Bridget Tubridy purchased land in Ferdinand Street, Birchgrove (an inner-city suburb of Sydney, next to Balmain). In true style as a 19th century property developer, she paid £87 for the land, borrowed £400, built a pair of terrace houses (with a party wall between them), subdivided and sold them for £350 each in October 1885, yielding a tidy profit. The terraces are basic two-storey terraces with two bedrooms upstairs. Today, they are worth more than $2 million each.

Birchgrove was not sewered at the time. The terraces had “water closets” (outhouses or “dunnies”) at the rear from which “nightsoil” was collected in sanitary pans with lids (“pans”). The nightsoil collector (the “dunny man”) used a narrow passageway (a “dunny lane”) to take the full pan from the “dunny” to his “dunny cart” and took it away to empty.

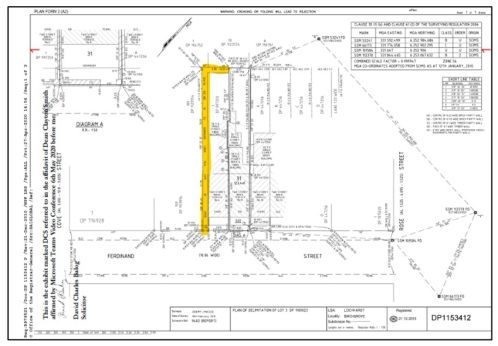

A passageway 3 feet 5 inches wide (1.045 metres) ran from Ferdinand Street, along the side of number 6 to the rear, when it took a right hand turn towards the rear of number 8 in the shape of an inverted “L” to give access to the outhouse (see the plan below).

When Miss Bridget Tubridy sold no. 8, she granted an easement for right of way over the passageway to the purchaser. When she sold no. 6, the passageway was not included in the land sold. It remained in her ownership as a separate parcel of land.

A sewer line was laid under the passageway in 1908, servicing the terraces. From the evidence, the passageway had probably not been used as an access to no. 8 for many years, although it had a gate on the street for much of the time. In recent years, the owner of no. 6 had used the passageway as an extension to their rear yard and had installed raised garden beds and a pergola on the path of the passageway.

These physical obstacles meant that the owners of no. 8 had no access to their rear yard using the passageway. They registered a plan of delimitation in 2010, which recorded a right of way over the passageway, to the benefit their property, reflecting the grant in 1885. This is the plan with the passageway highlighted in yellow:

When the owners of no. 6 purchased in 2011, they obtained a survey report which showed the passageway with raised garden beds built and a pergola on it. The report noted that “further investigation would be required to determine the ownership” of the land shown as passageway.

The owners of no. 6 repositioned the garden beds along the passageway in 2014. Later, they enclosed a roofed area across the passageway, effectively making it part of their room, without obtaining Council Approval.

In 2017, they owners of no. 6 made a Primary Application to acquire title to the passageway based on continuous possession that they and their predecessors in title had enjoyed over the passageway over many years, without reference to the right of way.

But when the title to the passageway issued, it had an easement for right of way noted upon it in favour of the owners of no. 8 (Smith - the defendants), because that easement was described in the plan of delimitation registered in 2010.

The Law and the Consideration

The owners of no. 6 (Sheppard – the plaintiffs) applied to the Court for an order extinguishing the easement for right of way.

They relied on the three grounds for extinguishment which are set out in section 89(1) of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW) (the “CA”):

- he right of way is obsolete, or unreasonably impedes the plaintiffs’ use of the land without securing practical benefit to the defendants; or

- the easement has been abandoned; or

- extinguishment of the easement would not substantially injure the defendants.

The main ground was that the easement had been abandoned.

Justice Parker referred to the leading Australian authority on abandonment of an easement - Treweeke v 36 Wolseley Road Pty Ltd (1973) 128 CLR 274 (High Court of Australia).

In that case, 36 Wolseley Road, the owner of land at that address in Point Piper, had the benefit of an easement for right of way 3 feet wide which had been created in 1927 when the land was subdivided. It gave access inside the side boundary of land owned by Mrs Treweeke (34 Wolseley Street) down to Seven Shillings Beach at Double Bay.

For forty years after it was created, the occupants of the block of units at 36 Wolseley Road did not use that right of way. They used an easier path to obtain access to the beach which ran across an adjoining property (over which they had no right of way). In 1967 that access was revoked, and they sought to assert the right of way over 34 Wolseley Street.

Mrs Treweeke applied to extinguish the right of way under s 89(3) of the CA, relying upon abandonment by non-user under s 89(1)(b).

The path over which the right of way ran had many obstructions: There were two rock ledges (one 4 feet high, the other 7 feet high), a stone retaining wall, an impenetrable bamboo plantation that Mrs Treweeke had planted, the framework of a swimming pool which she built in 1956 and a chain wire fence (to which 36 Wolseley had contributed).

Justice McTiernan observed “The non-user of the total length of the way can reasonably be put down to its precipitous condition at places. It is not reasonable to attribute non-user to renunciation of such a pleasant amenity as a path to the beach at Double Bay.”

Justice Mason, agreeing with Justice McTiernan that the right of way had not been abandoned, said: “In my view the non-user and other acts and omissions … were equally consistent with the existence of an intention not to use the right of way whilst an alternative means of access remained available.”

Justice Parker considered the effect of s 89(1A) of the CA, introduced in 2009, which states:

“For the purposes of s 89(I)(b), an easement may be treated as abandoned if the Court is satisfied that the easement has not been used for at least 20 years …”

He found that s 89(1A) applied only “in a case where there is no user of an easement for twenty years, and no other evidence to negate the intention of the person benefitting from the easement to abandon it”.

After considering these factors, Justice Parker found that the easement for right of way had not been abandoned:

- The lack of evidence of use the right of way by the prior owner of no. 8 from 1956 to 2008 could be explained as “she may have had no need to use it”, not an intention to abandon.

- Although the fencing at the rear did not contain a gate to allow the owners of no. 8 to access the passageway, this was not an intention to abandon. “The majority view in Treweeke was that the fencing off of the right of way, even when contributed to by the dominant owner, did not sustain an inference of abandonment.”

- Construction of obstacles across the right of way such as the raised garden beds and pergola was not an abandonment: “I see no real distinction between the circumstances in this case and the natural impassability of the right of way in Treweeke”.

- The fact that the right of way is not “readily trafficable” because of the garden beds and changes in height was not abandonment. The obstacles could be removed.

- One-off uses of the right of way by the owners of no. 8 to move a table, and access by surveyors, were “neighbourly acts” not evidence of user or an assertion of rights.

- Registration of the plan of delineation in 2010 with the right of way of way noted on it was a clear intention to retain the right of way.

- s 89(1A) “does not result in an abandonment if there is actual evidence of an intention not to abandon the easement in question” as there was in this case from 2010.

The Court then considered obsolescence as a ground for extinguishment of the right of way. It found that the easement was not obsolete for these reasons:

- The Court referred to Durian (Holdings) Pty Ltd v Cavacourt Pty Ltd [2000] NSWCA 28, in which Mason P said that when applying s 89(1)(a), a court must bear in mind that “the easement was created for an indefinite future and destined to enure in a changing environment”.

- The fact that the right of way had not been used for its original purpose to provide access to remove nightsoil since 1908 when the sewer was connected, did not make it obsolete. The terms were not limited to that use. It was a general right of way.

- The Court noted that “Such lanes are part of Sydney’s inner city heritage. They also continue to have a use in providing access”.

- After noting that passageways nearby had been restored for use, the Court said: “The right of way is capable of being restored to its former condition as a rear access laneway”. It was not demonstrated that “no reasonable use was possible”.

Finally, the Court considered whether the extinguishment will substantially injure the persons entitled to the easement in financial terms.

It found that its existence added value to no. 8: The owners of no.6 “did not challenge the [owners of no. 8] about their willingness to pay the cost of making the right of way usable, or lead any evidence to show that the right of way has no value”. In fact, the owners of no. 6 knew that if it were not encumbered, the land affected by the right of way was valued at $68,200 (stamp duty was paid on the Primary Application on that value).

Conclusions

This decision shows how hard it is to extinguish an easement for right of way.

In inner city Sydney, it may be close to impossible to extinguish a right of way over a passageway for these additional reasons:

- Old passageways, typically 1 metre wide, in inner city Sydney have found new uses. These days, they are being used to access rear yards, to avoid taking items such as bicycles, sporting equipment, bulky items, building material through the house and to store garbage and recycling bins.

- Old passageways have heritage significant if located in a heritage/conservation zone.

The owners of no. 6 who acquired title to the passageway are in the same position as their predecessor in title, Miss Bridget Tubridy, who never sold the passageway, possibly because it was almost worthless. An easement for right of way will sterilise the benefits of ownership of a passageway and devalue the land because it stymies rights to use it, except as a passageway.

The best advice for a purchaser of an inner city property is to have a surveyor prepare and register a plan of delimitation or boundary definition which shows the location of any passageway, immediately after the purchase is completed. This is especially recommended if no plan has ever been registered which shows a right of way over the passageway from which the land may benefit.

The registration of a plan that was the key to the owners of no. 8 retaining the right of way in this case, because by doing so, they asserted their rights from the date it was registered, in 2010. This was long before the owners of no. 6 asserted that the right of way had been abandoned.