There are no inheritance or estate taxes in Australia is the bold statement appearing on the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) website page headed Deceased estates.

But is that statement true or false? Have inheritance and estate taxes returned under different names following the abolition of inheritance taxes?

In this article we review –

- Death duties and estate duties that in the past, taxed inheritances in Australia

- Capital gains tax and super death benefits tax that potentially tax inheritances in Australia

Part 1 – What were inheritance taxes in Australia?

They say that death and taxes are the only two certainties in life.

But that cannot be said for death taxes / inheritance taxes in Australia. They are abolished in 1982, after raising considerable tax revenue for 100 years from 1880.

Every so often, there are calls to reintroduce inheritance taxes. So in this Part 1 we examine the inheritance taxes which have been abolished – which were called death duty and estate duty, and why they were abolished. In Part 2, we examine the new taxes that tax wealth on death which have replaced inheritance taxes.

Death Duty was introduced in NSW in the Stamp Duties Act of 1880. Not long afterwards, Victoria, Queensland and the other States followed and introduced their own Death Duty. It was also known as Probate Duty, Succession Duty, Estate Duty, Estate Tax, Inheritance Tax or Bequest Tax.

Death Duty was payable on the value of the deceased’s assets as at the date of death.

The Stamp Duties Act 1920 (NSW) (which replaced the Act of 1880) provided in section 101:

In the case of every person who dies [domiciled in New South Wales] … death duty shall be assessed and paid — (a) upon the final balance of the estate of the deceased; … and (b) upon all property forming part of the dutiable estate.

The “dutiable estate” was all-encompassing: the family home, other real estate, bank accounts, bonds, shares, jewellery, artworks and personal possessions were included. Debts due and payable were deducted to determine the “final balance of the estate”.

But that was not all. “All property forming part of the dutiable estate” included deathbed gifts and gifts made within three years before death in the dutiable estate (the “notional estate”).

When death duty was introduced in NSW, it was assessed at a flat rate of 1% of the value of the dutiable estate, for all persons dying on or after 1 July 1880.

In the Act of 1920, the rate was increased to flat 2% for small estates of up to £1,000, progressively increasing to a flat 20% for large estates, that is, estates with a value above £150,000. Lower rates applied when the estate was bequeathed to a widow, widower, dependent child, a public hospital, or a charity for the relief of poverty or for education.

In 1965, the rate was a flat rate of 3% for small estates up to $2,000, increasing to 15% for a mid-range estate of $54,000, and increasing to a top rate of 32% for large estates above $200,000 in value. The estate value for these tax brackets had not been raised since the 1940s despite inflation.

As a result, in the 1960s a tax planning industry grew up to assist wealthy people to restructure their assets to avoid high death duties. Some set up corporations and trusts in Australia, others moved their assets and domicile to tax havens such as the Bahamas, Cayman Islands, Monaco, Singapore and Hong Kong. Tax revenue from death duty started to fall.

But the real driver for abolition of death duty was that the value of the family home was included in the estate. With the high inflation of the 1970s, modest estates consisting of a family home and some savings were worth $54,000, attracting a flat 15% death duty. They were taxed twice – once when the home was left to the spouse, and again when left to the children.

Queensland led the abolition of death duty in 1978. As a result, significant numbers of retirees sold up their homes in Sydney and Melbourne and moved their domicile and money to the death duty ‘tax haven’ of the Gold Coast.

It was apparent to all that 100 years after it was introduced, death duty had become a political liability and abolition was a necessity.

Death duty was abolished in South Australia and Western Australia in 1980, in Victoria and New South Wales in 1981 and in Tasmania in 1982. Abolition was supported by the major political parties.

Estate Duty was an inheritance tax paid at the Federal level and was payable in addition to State death duty. It was introduced by the Australian Government to finance World War I.

The Estate Duty Assessment Act 1914 (Cth) which provided in section 8(1):

… estate duty shall be levied and paid upon the value … of the estates of persons dying after the commencement of this Act” [i.e. after 21 December 1914]

The dutiable estate comprised all real and personal property in Australia.

In addition, gift duty was payable at the Federal level on asset transfers by living persons, to discourage estate duty avoidance by giving the estate away before death.

The top tax rate was initially 20%. Later it was increased to 27.9%. When combined with death duty, estate duty meant that inheritance taxes as high as 50% of the value of the estate were payable, resulting in many family homes, farms and businesses needing to be sold or go into debt to pay the death taxes.

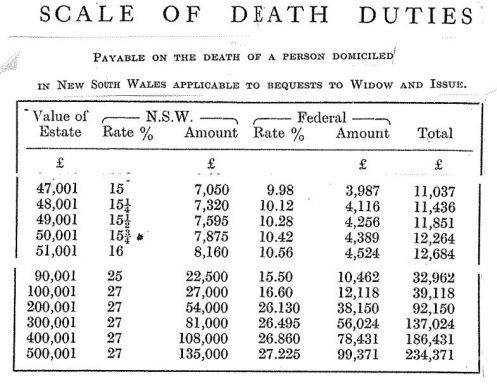

This scale from 1949 illustrates the NSW death duty and the Federal estate duty payable when an estate passed to a widow and children:

Estate duty was abolished on and from 1 July 1979, sixty one years after the end of World War I.

Australia has the distinction of being the first rich country in the world (along with Canada) to abolish inheritance taxes. Other counties are following this trend. 19 countries have abolished inheritance taxes, including: Israel inheritance tax in 1981, New Zealand estate duty in 1992, Portugal inheritance tax in 2004, Hong Kong estate tax in 2006 and Singapore estate tax in 2008.

Part 2 - Are Capital Gains Tax and Super Death Benefits Tax the new inheritance taxes?

When a tax is abolished, often a new tax is introduced to fill the revenue gap.

So it was that not long after the abolition of death duty and estate duty, a capital gains tax was introduced in 1985. Capital Gains Tax is a fairer tax than an inheritance tax because it taxes the capital gain, not the capital itself, when an asset is transferred. But it is still a tax!

When introducing the tax in 1985, the Treasurer took care to avoid it being seen as a new inheritance tax, coming so soon after the abolition of death duty and estate duty:

The Government has decided that the deemed realisation at death proposal, outlined in the draft White Paper, will not apply. Liability for tax in the case of death will be rolled over to successors, and will only be assessed on any subsequent disposal. Therefore the capital gains tax will not apply in the case of death. … [also] a complete exemption will apply to gains on the taxpayer's principal residence and reasonable curtilage” [Ministerial Statement by P.J. Keating on Reform of the Australian Taxation System 19 September 1985]

This is an outline of the legislation:

Capital Gains Tax (CGT) is payable when you dispose of an asset. Section 104.10 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) provides::

(1) CGT event A1 happens if you dispose of a CGT asset.

(2) You dispose of a CGT asset if a change of ownership occurs from you to another entity

Section 128.10 makes clear that capital gains tax is not payable in the case of death:

When you die, a capital gain or capital loss from a CGT event that results for a CGT asset you owned just before dying is disregarded.

Section 128.15 provides details:

(1) … what happens if a CGT asset you owned just before dying:

(a) devolves to your legal personal representative; or

(b) passes to a beneficiary in your estate.

(2) The legal personal representative, or beneficiary, is taken to have acquired the asset on the day you died.

(3) Any capital gain or capital loss the legal personal representative makes if the asset passes to a beneficiary in your estate is disregarded.

Australia is an exception in not treating death as a CGT event. In other countries where inheritance taxes have been abolished, death is treated as a capital gains taxing point for capital gains tax purposes.

In Australia, the taxing point comes later, when the inherited asset is sold.

The family home is exempt from CGT, even if it is sold after death, provided it is sold within 2 years of death. There is no need for a sale if the family home continues to be occupied by a person who inherits the family home because the main residence exemption from CGT applies.

And there is another exemption, which is that CGT does not apply as a general rule to assets acquired before 20 September 1985 (i.e. assets owned when CGT was introduced).

Illustration if the deceased purchased Commonwealth Bank shares when they first issued in September 1991, they would have paid $5.40 per share. If sold today, the sale price would be about $100 per share. The capital gain would be $94.60. A 50% discount is applied because the shares have been held for more than one year. So one-half, that is $47.30, is added to the taxable income of the estate (if sold by the legal personal representative) or of the beneficiary (if sold by the beneficiary who inherits the shares).

Super death benefits tax is payable if a deceased person’s superannuation balance passes as a lump sum to a non-dependent beneficiary. This tax applies from 1 July 2007.

Superannuation balances are left outside of a Will – they are not assets of the estate.

The superannuation balance is paid at the discretion of the trustee of the super fund, subject to a Binding Death Benefit Nomination (if one applies).

Super death benefits tax is payable by a non-dependent beneficiary on the superannuation balance they receive.

Where the trustee has the choice between paying the balance to a dependent or a non-dependent beneficiary, the super death benefits tax may be an important consideration in exercising the choice.

Most adult children will be non-dependents and therefore be liable to pay super death benefits tax if they receive a lump sum death benefit from their parent’s superannuation balance as an inheritance (they are not allowed to receive an income stream). The lump sum is added to their taxable income, and they pay super death benefits tax at these rates:

- On the taxable component of their super (taxed element), tax at the beneficiary’s marginal tax rate or 17% (15% + 2% Medicare levy), whichever is the lower; and

- On the taxable component of their super (untaxed element), tax at the beneficiary’s marginal tax rate or 32% (30% + 2% Medicare levy), whichever is the lower.

There are some circumstances where this tax may not apply, such as when the deceased and/or the beneficiary are older than 60 years.

As was the case with Death and Estate Duties, concessions apply to dependents. In this case, dependents pay no super death benefits tax on lump sums or income streams inherited. A dependent is defined as:

- the spouse or de facto spouse (of any sex), and any former spouse or de facto spouse

- a child of the deceased under 18 years old (and up to 25 years old if financially dependent) or without age limit if disabled; or

- an interdependent person, such as a person having a close personal relationship, living together, provided with financial support, or providing domestic support and personal care to the deceased

In summary, if there is no spouse or dependent child to leave the super to, if possible, the balance should be withdrawn before death so that it is distributed tax free under a Will, instead of passing to a non-dependent as a super death benefit who is facing a tax rate of up to 32%, a rate which has not been seen since the days death duties were payable!

Conclusion – Is Australia a tax haven for inheritance taxes

The ATO has a statement on its website. It is:

There are no inheritance or estate taxes in Australia

The statement is true, only if your affairs are structured to avoid Capital Gains Tax and Super Death Benefits Tax.