A Court will correct missing words or incorrect clause numbers in a contract because these are obvious errors. But how far will a Court go? What errors are obvious and what errors are not?

The NSW Court of Appeal recently examined three errors in a Contract for the Sale of Land. It decided that the contract should be rectified for two of the errors because the errors were obvious. It decided that the contract should not be rectified for one error because it was not obvious.

In this article, we examine the Court of Appeal decision of James Adam Pty Ltd v Fobeza Pty Ltd [2020] NSWCA 311 (Leeming JA, Bell P and Macfarlan JA agreeing) (3 December 2020)

The Facts

On 17 May 2019, Fobeza Pty Ltd agreed to purchase from James Adam Pty Ltd certain parcels of agricultural land at Woodstock, near Cowra in NSW for a price of $2,250,000. One parcel was proposed Lot 102 in an unregistered plan of subdivision.

The Contract contained these Additional Clauses which dealt with the subdivision:

39.0 Subdivision of Lot 1 in Deposited Plan 841539

39.1 The Vendor discloses that it has agreed to transfer 2001 square metres of the subject lot, being Lot 1 in DP 841539, to the Cowra Council and Rural Fire Services for use as its depot for the area.

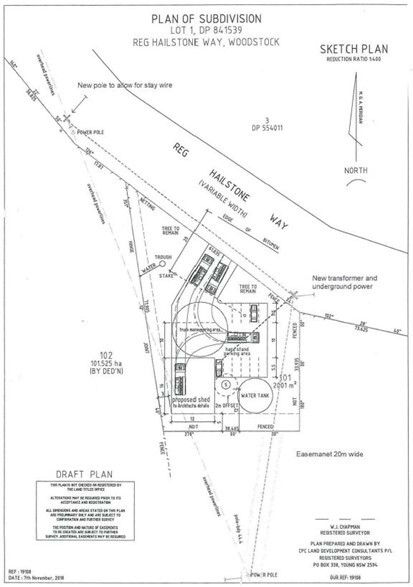

39.2 Annexed herewith is … a sketch plan of the proposed subdivision of the subject lot and in which is described proposed Lots 101 and 102 … proposed Lot 101 is excluded from the sale, and that proposed Lot 102 is included in the sale.

39.3 Completion of the contract is conditional upon the registration of the plan of subdivision in accordance with the sketch plan …

41.3 Purchaser’s right of rescission

a) The Purchaser may rescind this contract if the area of lot 102 in the plan of subdivision as registered is shown on the plan as being 2,100 sq. m or more, or if the location or the width of the easement are substantially different to that shown on the sketch plan set out in clause 39.

b) A right of rescission under clause 41.3(a) may only be exercised within 5 business days after notice is given under clause 42.2(d).

The sketch plan of the proposed subdivision was:

The area of Lot 101 is clearly marked as 2001 m² on the sketch plan.

The Court of Appeal corrected two errors in clause 41.3: first, it substituted Lot 101 for Lot 102; and second, it changed the reference to clause 42.2(d) to clause 41.2(d) because there was no clause 42.2(d).

This is what the Court of Appeal said about these errors:

These are two uncontroversial instances of “obvious errors” – where the literal meaning is an absurdity and it is obvious what the intended wording must have been. … these are good examples of where merely as a matter of construction the written form of the contract may and should be departed from. (paragraph 14, judgment)

When the plan of subdivision was registered on 22 October 2019, the area of Lot 101 was shown as 2205 m² on the plan, not 2001 m² as was marked on the sketch plan.

As this area was greater than 2,100 sq. m specified in clause 41.3., the purchaser gave notice of rescission of Contract and required a refund of the deposit paid of $112,500.

The purchaser sought a declaration that it had validly rescinded the Contract and sought the return of the deposit. The vendor by cross-summons sought an order for specific performance of the Contract (as rectified).

The vendor’s case rested upon whether or not it could rectify the Contract to correct the surveyor’s error on the sketch plan that the area marked for lot 101 was 2205m², not 2001 m².

(To clarify) – The dimensions of Lot 101 on the sketch plan were the same as the dimensions of Lot 101 on the registered plan – and the area was always 2205m². The error was that on the sketch plan the area was marked as 2001 m², when it should have been marked as 2205m².

Was the Court willing to rectify the error in the land area?

The Court of Appeal accepted that the literal construction of clause 41.3 was absurd. This was because registration by James Adam of a plan of subdivision “in accordance with the sketch plan” would always entitle Fobeza to rescind the contract, as according to the precise lengths and bearings of the parcel of land shown in the sketch plan, the area of Lot 101 always exceeded 2100 m².

The Court of Appeal applied the common law doctrine of contractual construction in which an objective view is taken of the intention of the parties. It has two limbs.

The Court of Appeal said that the error was “sufficiently absurd or inconsistent to engage the first limb of the doctrine of rectification by construction”.

However, the Court of Appeal said that the second limb was not satisfied because it was not possible to objectively determine which of a number of possible constructions of clause 41.3 the parties intended, because none were obvious:

In order for the contract to be rectified as a matter of construction, it is necessary for it to be self-evident what the objective intention is taken to have been.

This is not a case of a mere slip, where a word is missing, a concept confused with its antonym, or a clause misnumbered or incorrectly cross-referenced in the contract. There is no clear or self-evident solution to the absurdity that the figure of 2100m2 presents.

The parties’ written bargain was informed by the erroneous area on the surveyor’s sketch plan, but where neither appreciated that there was an error, it is impossible as a matter of construction to impute to them how their bargain would have been framed had the error not been made. (paragraphs 72 and 73, judgment)

Note: In this case, there were several possible alternatives, such as the figure being 2315 sq. m being 5% above the actual area of 2205, just as 2100 was 5% above the stated figure of 2001; or 2100 sq. m instead of 2001 sq. m on the basis that 2001 was a typographical error.

The Court of Appeal upheld the trial judge’s decision that the Contract had been validly rescinded and the deposit was to be returned.

Conclusion

An application for rectification of a contract will be defeated if different alternatives are shown as possibilities for the term in the contract that it a party desires to rectify.

The existence of alternatives means that the error is not obvious. As such, a Court will not correct the error.